“Zombie ships” represent one of the most advanced forms of maritime deception, where ships hide behind false digital identities and recycled registrations to escape legal scrutiny. These tactics underscore the pressing need for enhanced global enforcement, more effective verification tools, and real-time maritime intelligence.

As regulations struggle to keep pace, detection of illicit shipping activity increasingly depends on specialised tracking platforms and robust market oversight, areas where Pole Star Global continues to lead. Without decisive intervention, identity laundering – such as the use of zombie vessels – risks becoming entrenched in global trade, eroding both safety and trust across the maritime industry.

This article by Pole Star Global explains what zombie ships are and how they are used to circumvent sanctions. It also outlines methods for detecting zombie vessels to enhance regulatory oversight, illustrated with real-world examples.

Key Statistics and Insights on Zombie Ships

- Definition: Zombie ships assume the identity of scrapped or decommissioned vessels by reusing their IMO/MMSI numbers.

- Scale: Numbers have been rising rapidly since 2022, driven by expanded Western sanctions.

- Purpose: To carry our illicit activity and evade detection. For instance, carrying sanctioned crude (Russia, Iran, Venezuela), arms and other illicit goods.

- Risks: Old ships intended for scrapping are more prone to accidents (e.g., the Pablo explosion in 2023, which killed three crew members and posed a spill risk of up to 700,000 barrels), presenting significant environmental and safety concerns. Plus, geopolitically, zombie ships undermine sanctions, fund rogue regimes, and destabilise regions.

Detection Challenges:

- Ghost trails from “dead vessels” complicate ownership tracking.

- Many operate without a known owner, flag, or insurer.

Case Studies Highlighted:

- TOR: Dismantled in 2018; identity stolen and used to transport Venezuelan crude.

- FREESIA I: identity hijacked by APUS; used to load 140,000 tonnes of HSFO.

- URANUS: Officially scrapped, but still active. Ship regularly uses AIS spoofing to hide activity.

- VARADA: Another zombie vessel that has had long gaps in AIS reporting, showing signs of AIS spoofing, and Iran-linked STS transfers.

- EM LONGEVITY: Scrapped in 2021; reappeared in 2023 and still active in 2025, supplying Chinese “teapot” refineries.

Regulatory Response:

- OFAC (2025) banned the reuse of IMO numbers from scrapped vessels.

- Push for satellite verification with AI, cross-border data sharing, and AIS integrity checks.

Pole Star Global’s Approach:

- PurpleTRAC and Deep Blue Intelligence detect falsified identities. The “Tools, Targeting, Training” strategy equips compliance teams to spot zombie ships more effectively.

Want to Learn More?

- CASE STUDY 1: Island Oil Ltd: How to Secure Compliance and Optimise Vessel Screening

- ARTICLE 1: AIS Spoofing Research Unveils 4 Main Typologies: A Complete Guide

- ARTICLE 2: CRUDE MEASURES: HOW RUSSIA’S DARK FLEET EVADES SANCTIONS

- USE CASE: Dark Vessel Detection

What are Zombie Ships?

Zombie ships are vessels that take on the identity of scrapped ships, adopting their names, IMO numbers, or MMSIs to conceal illicit activities. By manipulating or switching off their Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracking, these ships effectively vanish from conventional monitoring, making their movements and operations difficult to trace. By assuming the identity of recently decommissioned vessels, they project a façade of legitimacy.

This practice, often described as maritime identity laundering, has evolved into a sophisticated strategy and a systemic enabler of large-scale sanctions evasion.

At the core of these operations are opaque ownership structures, collectively referred to as the “Shadow Fleet.” Zombie ships sit at the extreme end of this spectrum, posing a growing threat to maritime safety, regulatory enforcement, and the credibility of international sanctions regimes.

How Many Zombie Ships Are There?

Since 2022, AIS spoofing and maritime identity hacking have surged, driven in large part by the expansion of Western sanctions. While the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has begun to intervene, enforcement efforts are struggling to keep pace with the increasingly sophisticated tactics employed by bad actors, such as the use of zombie vessels.

The use of zombie vessels has grown in recent years, and the team at Pole Star Global is actively monitoring the trend. For example, a recent search of all vessels listed as ‘broken up‘ but still transmitting within the past 14 days identified 149 ships, giving a clear indication of the scale of zombie vessel activity.

How do Zombie Ships Work?

By hijacking the IMO or MMSI numbers of decommissioned (scrapped) vessels, bad actors assume a veneer of legitimacy, broadcasting AIS signals under this stolen identity. This enables illicit operators to:

- Move sanctioned oil, including Venezuelan, Russian, and Iranian crude.

- Smuggle illegal cargo, such as arms.

- Circumvent sanctions or blacklists applied to specific ships, flags, or owners.

Ships operating without any identity are a clear red flag for authorities. However, by assuming the identity of a “clean” vessel, flying the flag of a neutral country, registering under a neutral owner, and even securing insurance from legitimate providers, these operators drastically reduce suspicion and bypass automated screening systems.

Plus, when looking at how vessel ownership is tracked, ships masquerading as “dead vessels” leave an ownership trail that points to a ship that no longer exists. Think of it as like a ghost trail, which complicates oversight and enforcement.

Although vessel identity theft predates the 2022 sanctions surge, it has flourished amid expanding embargoes. These falsified identities are used in combination with other illicit tactics, including:

- Broadcasting false coordinates.

- Disabling transponders to create blackout periods during high-risk operations.

The result is a fleet operating without clear jurisdiction or visibility, shrouded in opaque ownership, forming a digital ghost armada that facilitates illicit trade on a global scale.

Why Are Zombie Ships Dangerous?

Zombie vessels present severe safety, environmental, and geopolitical risks.

Environmental and Safety Risks

Operating without proper inspection or insurance, zombie ships carry a heightened likelihood of accidents and environmental disasters. Should an incident occur, such as an oil spill, the anonymity of these vessels raises serious questions about accountability. Plus, with no insurance coverage, there’s no financial recourse.

To add to this, these old vessels were meant to be scrapped due to reaching the end of their service life. Reusing such aged and structurally compromised ships makes accidents more probable.

Zombie vessels also pose acute safety hazards. Their use of AIS spoofing can interfere with collision-avoidance systems, dramatically increasing the potential for maritime accidents and environmental disasters.

Acting as a stark reminder of these environmental and safety risks is the explosion of the Pablo oil tanker off the coast of Malaysia on 1 May 2023. The Pablo, built in 1997, was slated for scrap five years ago but instead became part of Iran’s shadow fleet. The vessel, which was nearly empty after unloading cargo in China, was navigating the South China Sea en route to Singapore when it caught fire 37.5 nautical miles northeast of Tanjung Sedili, Johor, Malaysia.

The explosion is thought to have been caused by a build-up of flammable gas in the empty hold, ignited by a fire on the upper deck. The ship’s old age and the fact that it has been identified as operating as part of the “shadow fleet” raised concerns about potential safety issues and inadequate maintenance. The incident tragically claimed the lives of three crew members and resulted in oil washing up on Indonesian shores.

Tracking the vessel via Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC software revealed that, following the incident, the ship waited offshore for months as authorities struggled to identify the owners and insurers. Without a known insurer, Malaysian authorities had to manage the incident themselves. Had the tanker been carrying its full capacity of 700,000 barrels of oil, the environmental and economic damage to the Malacca Strait – a major shipping route with rich fisheries and productive coastal ecosystems – could have been catastrophic, amounting to billions of dollars.

This incident underscores the profound risks posed by a flotilla of ageing, unregulated vessels transporting Russian, Iranian, and Venezuelan crude, highlighting the urgent need for stronger oversight, tracking, and enforcement.

Geopolitical Risks

From a geopolitical perspective, ghost vessels undermine international sanctions regimes, weakening diplomatic pressure on rogue states and eroding trust between allies enforcing these measures. To conceal their operations, these ships often disable their AIS, spoof vessel identities, or conduct deceptive ship-to-ship transfers, making them difficult for coastguards and naval forces to track. In conflict zones, sailing under false identities also raises the risk of misidentification, with potentially tragic consequences.

By transporting illicit goods, such as sanctioned oil and arms, ghost ships directly fund rogue regimes, support terrorist groups or militias, and destabilise entire regions.

How Can Authorities Detect Zombie Ships?

In April 2025, OFAC banned the reuse of IMO numbers from decommissioned vessels and increased oversight of identity changes. This heightened scrutiny called for robust countermeasures based on multi-source data, including:

- Satellite verification with machine learning to detect physical inconsistencies;

- Cross-border data sharing to flag suspicious activity in near real-time;

- AIS signal integrity checks integrated into port state control.

Yet, regulatory solutions, such as those employed by OFAC, may not by themselves resolve the issue. For example, when OFAC sanctioned the ship Uranus (see section below: “Recent Case Studies: Vessels Operating Under False Identities”), it effectively targeted the vessel’s digital identity. However, attempting to sanction every zombie vessel in this way would quickly become unmanageable for screening systems, while offering little more than a minor inconvenience to illicit actors, who could simply select another vessel from the list. A more effective approach is to leverage vessel screening and tracking tools capable of identifying a ship’s current operational status – a capability Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC has provided from the outset.

This highlights the value of a “Tools, Targeting, and Training” strategy. That is, beyond monitoring tools and watchlists for tracking the Dark Fleet, this strategy also incorporates the latest tactics employed by threat actors into its training. This empowers compliance officers worldwide to detect, assess, and respond to suspicious maritime activity with greater precision and confidence.

Tools, Targeting, and Training Strategy: How to Identify Zombie Ships and the Dark Fleet

- Tools → monitoring systems and watchlists for tracking the Dark Fleet.

- Targeting → focusing on current threat-actor tactics and vessel behaviours.

- Training → equipping compliance officers with the skills to identify and respond to suspicious activity.

From a tools perspective, PurpleTRAC, together with the Deep Blue Intelligence platform (a platform provided by Pole Star Global and key partner, Blackstone Compliance Services), combines expert intelligence with detailed vessel profiles to uncover the real story behind each “zombie” ship. (This is demonstrated in the section below, Recent Case Studies: Vessels Operating Under False Identities.)

What is the Difference Between a Zombie Ship and a Dark Ship?

A zombie ship is a vessel that assumes the identity of a ship that no longer exists (usually scrapped, sunk, or otherwise taken out of service). It is identity theft carried out by reusing the ship’s MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity) or IMO number, making it appear legitimate on tracking systems.

This method is attractive to sanctions evaders because there is no risk of the real ship “showing up” to expose the fraud, as the original vessel has been dismantled or destroyed.

A dark ship (or a vessel “going dark”) is a ship that deliberately disables or manipulates its AIS transponder so it cannot be tracked. This typically occurs during suspicious activity, such as during ship-to-ship transfers, entering sanctioned ports, or transporting illicit cargo. The vessel still exists and is operational; it is simply rendered “invisible” to monitoring systems for a period of time.

Key difference:

- Zombie vessel = fake identity (pretending to be a ship that no longer exists).

- Dark ship = no identity (hiding by turning off tracking).

Why Are Zombie Ships Increasing in Number?

Zombie vessels are rising in popularity because they provide a simple, low-effort way to bypass sanctions. The process is straightforward: take a list of scrapped tankers, extract their last reported MMSI, and reuse those identities. Compared with hijacking or duplicating the identity of an active vessel, which is a higher-risk tactic known as MMSI hijacking or duplication, this method is far easier. Pole Star Global‘s PurpleTRAC is designed to detect both.

“In my view, this is a crude and easily detectable evasion tactic. PurpleTRAC clearly indicates a vessel’s status, so if a ship transmitting data is listed as scrapped or out of service, that should be treated as a serious red flag and trigger enhanced due diligence. – David Tannenbaum, Director of Blackstone Compliance Services

A more sophisticated evolution of the tactic could involve collusion with local scrappers, ensuring vessels remain listed as “active” on paper even after being broken up. This would make identity theft far harder to detect. It is not difficult to imagine a scrapper in Bangladesh accepting a small payment to “keep a vessel alive” in records. However, to date, there is no evidence that such practices are taking place.

Recent Case Studies: Vessels Operating Under False Identities

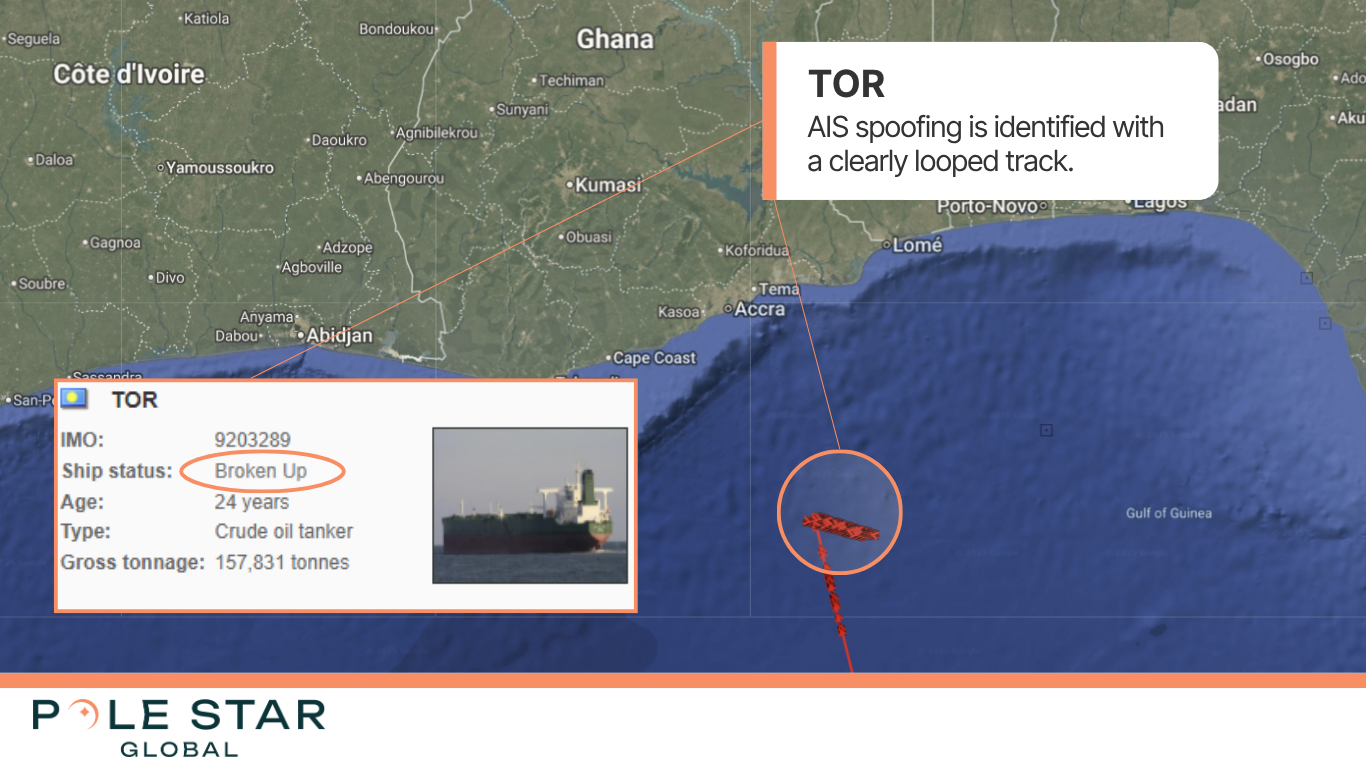

TOR (IMO 9303289)

The vessel VLCC VERONICA III (9326055) assumed the identity of TOR (IMO 9203289). However, analysis using Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC software revealed that Tor had been dismantled in 2018 (see image below).

Analysis by Pole Star Global and key partner Blackstone Compliance Services highlights that the ship TOR frequently disabled its AIS system in Malaysia’s high-risk ship-to-ship transfer zones. AIS disablement periods last from one day to a week. For example, between 27 July and 26 August 2024, the vessel transmitted false location data off the west coast of Africa near 03° 37.384′ N, 000° 50.091′ E. While Sentinel-2 satellite imagery does not cover this area, the AIS data reveals a looped track, which is strong evidence of deceptive manoeuvring (see image above). During these operations, the vessel was transporting crude from Malaysia to China.

In another case, between April and May 2025, the vessel conducted three ship-to-ship transfers of high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) from smaller vessels, including LR1 Tailwinds (IMO 9280354), the LR2 tankers Colon (IMO 9503574), and Oriental Pearl (IMO 9281011). These operations were independently verified using satellite imagery, as AIS signals in Venezuelan waters are often sparse or intentionally misleading when zombie fleet tactics are employed. The cargoes were traced back to Venezuela’s El Palito and Cardón refineries.

This activity aligns with the export strategy typically used by Venezuelan-linked tankers: large crude carriers, frequently operating under recycled or spoofed vessel identities, load Venezuelan crude or HSFO in stages. Once fully loaded, they set sail for Asian markets such as China, or other distant destinations, leveraging the obfuscation provided by AIS manipulation and identity fraud to evade detection.

FREESIA I (IMO 9159660)

The SUEZMAX APUS (IMO 9280885) is currently transmitting under the identity of the inactive vessel FREESIA I (IMO 9159660), appearing in port records as if FREESIA I were loading at the José Oil Terminal. In reality, APUS loaded approximately 140,000 tonnes of high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) from the Port of José. The vessel subsequently transited the Sunda Strait, but its current destination remains unknown, underscoring the challenges posed by identity spoofing in monitoring high-risk maritime activity.

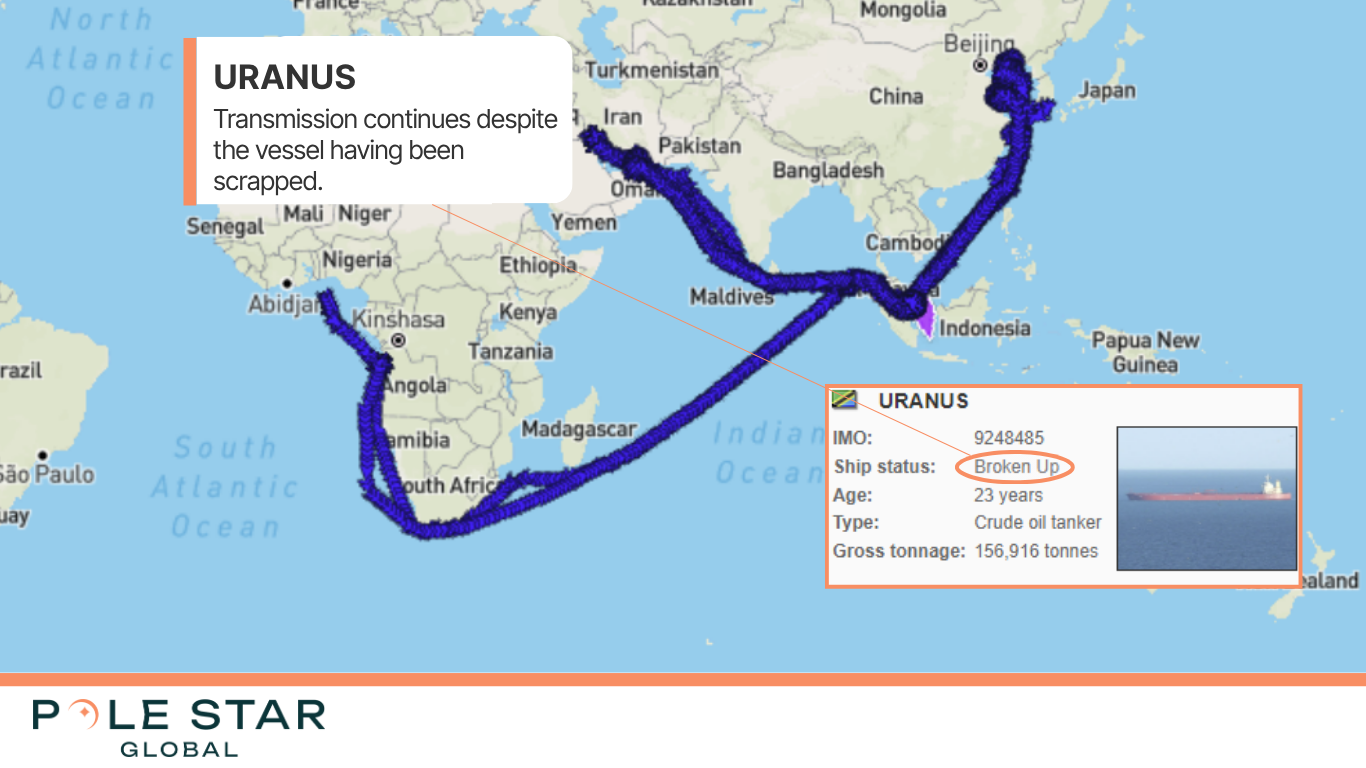

URANUS (IMO 9248485)

URANUS (IMO 9248485) has appeared in the Koban designations, despite being officially listed as scrapped, indicating that OFAC is targeting not only physical vessels but also their digital identities.

Although scrapped, URANUS continues to operate according to AIS data. Its movement history raises serious red flags, showing activity across the Gulf of Oman, the Arabian Sea, along the coast of Malaysia, and traversing the East and South China Seas, with a pause near the Shandong Sea.

There is also evidence of deliberate non-AIS reporting, including a reporting gap of 187 days and 14 hours on 13 October 2024, and another gap of 7 days and 20 hours on 7 June 2025 in Syrian territorial waters. These patterns suggest intentional obfuscation.

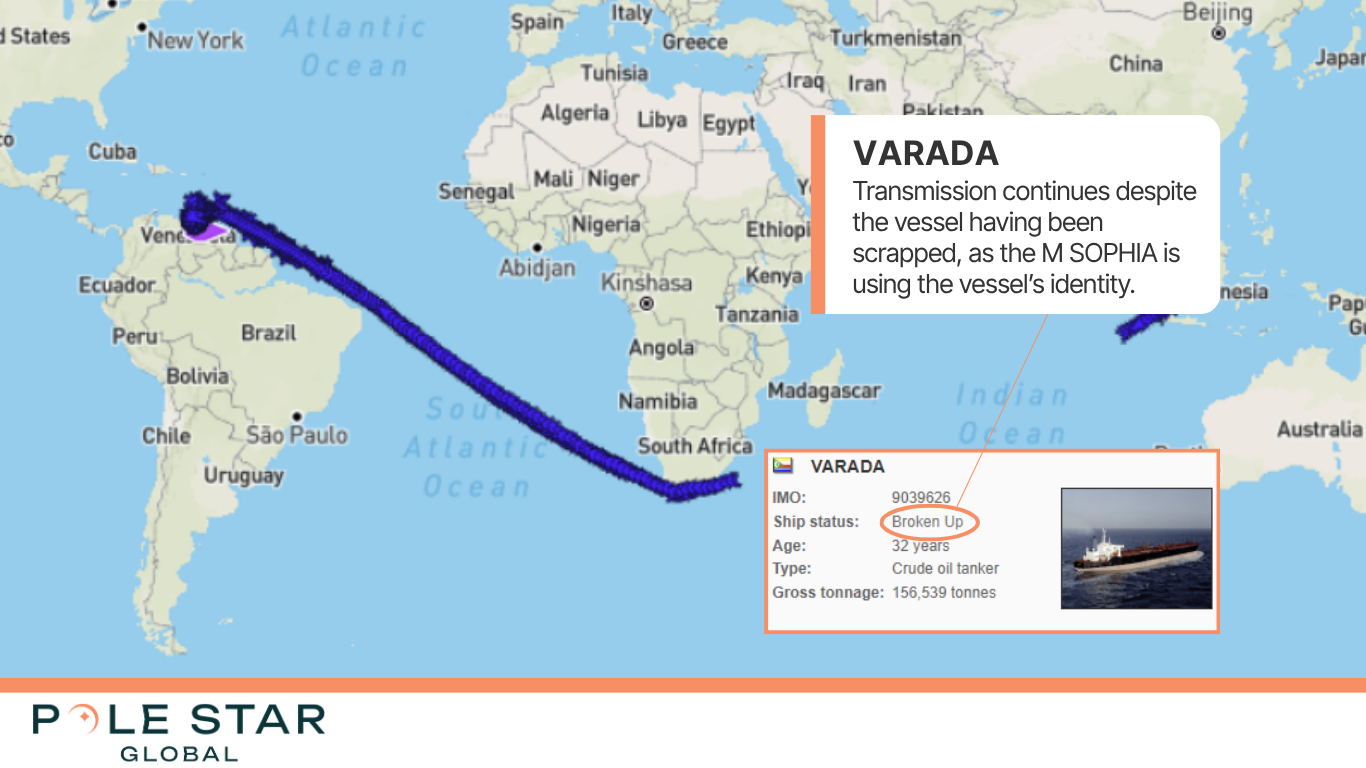

VARADA (IMO 9039626)

Another vessel identified as a zombie ship is the VARADA (IMO 9039626), recently flagged for suspicious activity. At 32 years old, the ship is well beyond the typical scrapping age and sails under the Comoros flag of convenience.

On the surface, the VARADA appears to operate like other dark fleet vessels, transporting barrels of sanctioned crude from countries such as Russia, Iran, and Venezuela. For instance, in one journey, the vessel departed Venezuela’s José Terminal, crossed the Atlantic, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and transited the Indian Ocean before entering Malaysian waters on 18 April. At this point, the vessel’s AIS tracking signals went dark. With its destination listed as “for orders” and deep draft readings suggesting a heavy oil load, the ship’s activities quickly raised red flags.

The waters off Malaysia’s east coast are a major transhipment hub, where dark fleet vessels often carry out ship-to-ship transfers before crude reaches Chinese refineries, enabling illicit cargo to slip past conventional monitoring systems.

The vessel currently posing as the VARADA is believed to be the M SOPHIA (IMO 9289477), previously sanctioned by the US during the Biden administration. The M SOPHIA appears to be transmitting signals that place it in the Gulf of Guinea, but these are likely falsified. The vessel fits the profile of a dark ship: it has no known owner or insurer and appears to operate without a flag.

M SOPHIA frequently disables its AIS (Automatic Identification System) for extended periods, particularly in high-risk ship-to-ship (STS) zones off Malaysia, often while handling Iran-related cargo. Some of these AIS gaps have lasted over a month. Between 14 February and 9 April 2023, the vessel spent considerable time in the Ceuta STS zone. Sections of its track suggest deliberate signal spoofing, while others appear consistent, making it difficult to determine whether the movements represent legitimate STS transfers or deceptive activity. In either case, the behaviour appears economically purposeless.

The vessel’s information was last refreshed on 3 October 2024. Between 14 June and 28 August 2024, M SOPHIA underwent another prolonged spoofing event off the west coast of Africa, near Nigeria. This region is a Sentinel-2 satellite dead zone, yet the vessel’s AIS data exhibits clear synthetic patterns, closely matching known spoofing behaviours in the area.

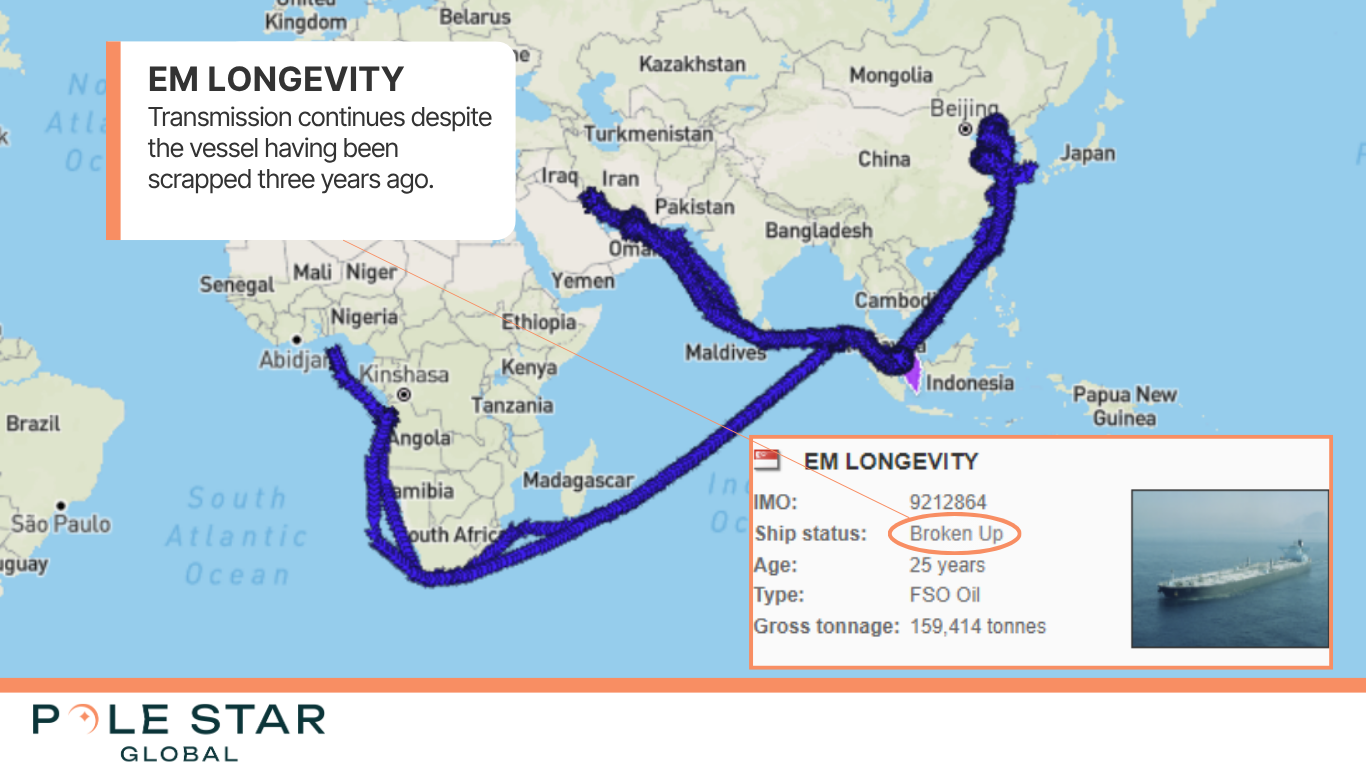

EM LONGEVITY(IMO 9212864)

The EM LONGEVITY, formerly flagged in Singapore, was believed to have made its final voyage nearly four years ago. Built in 2000 as a very large crude carrier, it was officially recorded to have been sent to a Bangladeshi scrapyard in December 2021, marking the end of its operational life.

Yet in September 2023, a tanker using the EM LONGEVITY’s IMO number reappeared at a terminal in Dalian, Liaoning Province, carrying crude and preparing to unload. After partially discharging its cargo, it crossed the Yellow Sea and docked at Yantai, Shandong Province, according to satellite imagery and ship-tracking data. Remarkably, as of August 2025, the EM LONGEVITY continues to operate along the Dalian route.

Persistent tracking by Pole Star Global reveals that the vessel’s Group Beneficial Owner and insurer remain unknown, which is a critical red flag indicating potential illicit activity.

Between April and August 2025, the tanker repeatedly navigated the Strait of Malacca, passed Singapore, and proceeded north toward China via the Yellow Sea, transiting between Liaoning and Shandong provinces. These waters are home to numerous so-called “teapot” refineries, independent plants that have increasingly relied on discounted crude from sanctioned producers, particularly Iranian oil. The EM LONGEVITY’s movements suggest it may be playing a direct role in facilitating this high-risk supply chain.