The “dark fleet,” also known as the shadow fleet, is a network of oil tankers and cargo vessels that operate outside conventional regulations and international oversight. These ships often evade detection by turning off AIS transponders, using older vessels, and registering under opaque ownership structures in countries with lax maritime laws. Predominantly linked to Iran, Russia, and Venezuela, the dark fleet has grown significantly in recent years, particularly in response to sanctions on Russian oil following the invasion of Ukraine.

This article explores the scale and composition of the dark fleet, highlighting the top flag states, operational methods such as ship-to-ship transfers, and emerging tactics such as AIS spoofing. It examines how international sanctions, including those enforced by the US, UK, and EU, affect these vessels and their operators, and discusses the risks posed by ageing, poorly maintained ships to both global shipping and environmental safety.

Additionally, the article explains how authorities and stakeholders identify and track dark fleet vessels, the role of grey fleet ships, and real-world examples of shadow fleet incidents. It also considers the economic impact of the dark fleet on sanctioned countries, particularly Russia, and outlines strategies for enforcement and monitoring to curb illicit maritime activity.

Key Statistics and Insights on Bunkering

Definition and Scope

- The dark fleet refers to a network of oil tankers and cargo vessels operating outside standard international regulations.

- Methods of evasion include turning off AIS transponders (“going dark”), using older or recycled vessels (“zombie ships”), opaque ownership, and ship-to-ship transfers to obscure cargo origin.

Size and Composition

- Approximately 600–1,000 vessels operate in the dark fleet, representing roughly 10% of the global fleet of large oil tankers.

- The fleet is roughly evenly split between Russia and Iran, with Venezuela also contributing.

- Many vessels are over 15 years old and inadequately maintained.

Flag States & Legal Loopholes

- Top flags: Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands, Malta, and Russia.

- Most are “flags of convenience,” allowing lax regulation, cheap registration, and easier evasion of sanctions.

Sanctions and Enforcement

- The dark fleet enables sanctioned countries, especially Russia, to bypass oil price caps and sanctions, sustaining economic activity despite restrictions.

OFAC and international regulators have intensified efforts, including targeting individual vessels; supporting infrastructure (P&I clubs, classification societies, ship brokers), and “Zombie vessels” using recycled IMO numbers

Economic Impact

- Russian shadow fleet exports reached 4.1 million barrels per day in June 2024 (~70% of Russia’s seaborne oil exports).

- Enforcement measures in early 2025 contributed to a 19% year-on-year decline in oil and gas revenues.

- Sanctions are starting to affect Russia’s broader economy, including production of excavators (down 48.6%) and titanium products (down 45%).

Operational Risks

- Ageing vessels, AIS disabling, and poor maintenance increase accident and environmental risks.

- Notable incidents: Pablo tanker fire (May 2023, South China Sea) – 3 crew lost; potential billion-pound environmental damage avoided.

Identification & Tracking

- Tools like Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC combine satellite imagery, AIS, and historical patterns to flag high-risk vessels.

Want to Learn More?

- CASE STUDY 1: Island Oil Ltd: How to Secure Compliance and Optimise Vessel Screening

- ARTICLE 1: AIS Spoofing Research Unveils 4 Main Typologies: A Complete Guide

- ARTICLE 2: CRUDE MEASURES: HOW RUSSIA’S DARK FLEET EVADES SANCTIONS

- USE CASE: Dark Vessel Detection

What is the Dark Fleet?

The “dark fleet,” also known as the “shadow fleet,” refers to a collection of ships, primarily oil tankers, that operate outside normal regulations and international oversight. These vessels use various tactics to avoid detection, including:

- Turning Off AIS Transponders: Ships often disable their Automatic Identification System (AIS), making them invisible to standard tracking services. This practice, known as “going dark,” hides the vessel’s location and is the origin of the term “dark fleet” or “shadow fleet.”

- Using Aged Vessels: Many ships in the dark fleet are older, around 15 years or more, and would normally have been retired. In some cases, ships even adopt the identities of scrapped vessels. Such vessels are called “Zombie Ships.”

- Opaque Ownership: Dark fleet vessels are frequently registered under shell companies in jurisdictions with lax oversight, making it difficult to hold anyone accountable.

- Ship-to-Ship Transfers (STS): Sanctioned oil is often transferred between tankers at sea to obscure its origin and destination.

The dark fleet has existed for years, with roots in Iran and Venezuela. However, it has grown significantly since Russia invaded Ukraine, allowing Russian crude oil carriers to bypass sanctions and sell oil above the $60 price cap imposed by the US, UK, and EU.

How Many Dark Fleet Vessels Are There?

The number of vessels in the dark fleet has fluctuated with each new regulation, and has changed even more dramatically following the Russian oil ban and price caps.

According to CNN, the shadow fleet comprises roughly 600 vessels, representing about 10% of the global fleet of large oil tankers. This figure is supported by data from Pole Star Global, in partnership with Blackstone Compliance Services.

But how well do people actually understand the scale of this fleet? Last year, Pole Star Global asked respondents to guess the total number of vessels in the dark fleet. Most overestimated, suggesting around 25%, while a sizeable group underestimated, putting the figure between 0.1% and 1%. Yet a significant portion of respondents correctly estimated around 10%, suggesting that awareness of the dark fleet is increasing.

What Countries do Dark Fleet Vessels Come From

The top five flags for dark fleet vessels are:

- Panama

- Liberia

- Marshall Islands

- Malta

- Russia

Most of these countries are considered flags of convenience, which means:

- They allow foreign owners to register ships easily.

- They have less strict regulations on safety, labour, and environmental standards.

- Registration is cheaper than in countries with stricter maritime oversight.

These looser rules make it easier for operators of the dark fleet to:

- Evade sanctions by concealing ownership or the origin of cargo.

- Reduce costs by bypassing strict safety or maintenance requirements.

It is worth noting, however, that Russia is not a typical flag of convenience, yet it still appears in the top five. This is largely because:

- Some ships are domestically registered in Russia.

- Due to sanctions, Russian-flagged tankers may operate more covertly, sometimes turning off AIS or conducting ship-to-ship transfers to conceal their activities.

- The concentration of these flags in the dark and grey fleet demonstrates how legal loopholes and lax jurisdictions are exploited for high-risk or sanctioned shipping. It also highlights why monitoring these fleets is particularly challenging for regulators.

What Significant Changes Has the Dark Fleet Undergone in the Last Year?

Identifying dark fleet vessels has not become significantly more difficult. Currently, data from Pole Star Global, in partnership with Blackstone Compliance Services, indicate that around 1,000 vessels are operating in this space, roughly split 50:50 between Iran and Russia.

Another noticeable development is the emergence of crossovers, with Russian vessels transporting Iranian oil and vice versa.

Then there’s AIS spoofing, which has become increasingly common. As more vessels disable their AIS (Automatic Identification System), ship-tracking operations become significantly more difficult. To complicate matters further, some bad actors are now using more advanced spoofing techniques.

Iranian vessels, however, often rely on traditional obfuscation methods, suggesting they do not feel significant pressure from sanctions. In response, OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) has intensified sanctions against Iran following the events of 7 October 2024. These sanctions target individual vessels, frequently linking them to Iranian proxies or IRGC front companies.

Russian operations, by contrast, remain relatively stagnant. Russian vessels have been pushed out of Greece and the Gulf due to increased enforcement by the Greek Navy, which is implementing price caps and sanctions more strictly.

When it comes to sanction enforcement, OFAC’s actions appear to have the most substantial impact. For instance, further reports from Pole Star Global’s partner, Blackstone Compliance Services, indicate that UK sanctions have not significantly altered Russian operations.

Regarding dark fleet vessels transporting LNG, Russia is attempting to restart its sanctioned LNG plant. Although OFAC designated the plant within two weeks, dark fleet LNG shipments continue despite minimal activity at the facility. As such, LNG carriers remain high-risk assets.

OFAC continues to update sanctions aimed at restricting dark fleet activity, influencing operational behaviours in the ongoing cat-and-mouse dynamic of evasion and enforcement. A notable tactic has been to publicly sanction a tanker and warn that any dealings with it will trigger further sanctions, a strategy that has so far effectively deterred engagement.

More recent measures include the April 2025 ban on reusing IMO numbers from decommissioned vessels and increased oversight of vessel identity changes. These actions are intended to track and restrict the movement of “zombie vessels” involved in illicit activity.

Further updates in August 2025 show that OFAC is now targeting the infrastructure that supports the dark fleet, including P&I clubs, classification societies, flag registries, corporate formation agents, and ship brokers.

The full impact of these measures on dark fleet operations remains uncertain; only time will reveal how vessel behaviour and operational strategies may shift in response.

How Will the Dark Fleet Evolve as International Pressure on Sanctioned Countries Intensifies?

The team at Pole Star Global anticipates that the dark fleet will continue to expand until it reaches capacity. However, there are limits to the amount of oil that Iran and Venezuela can export. A key factor will be tanker availability and whether countries such as China and India resume importing Iranian oil.

Tankers are increasingly being used as floating storage units, making it difficult to assess overall capacity. Teams at Pole Star Global, together with their partner Blackstone Compliance Services, are adding new vessels to the dark fleet weekly. It remains unclear, however, whether these ships have always been part of this trade or are returning after a period of inactivity.

It is also important to note that illicit operators will eventually need to replace ageing tankers, particularly as some become “toxic” due to sanctions. OFAC is focusing on reporting suspicious tanker sales, which often involve the recycling of older vessels.

Are There Any Common Misconceptions About the Dark Fleet?

As noted earlier, many people underestimate the size of the dark fleet, which accounts for around 10% of all tankers – potentially numbering in the hundreds.

There is also a common misconception that this activity is predominantly Russian; in reality, it is roughly evenly split between Russia and Iran, with substantial involvement from the latter.

Why is It Important to Identify and Stop Vessels Operating Within the Dark Fleet?

Between 22 February 2022 and 11 January 2024, countries and organisations worldwide imposed over 16,000 restrictions on Russian individuals. In addition, around 9,300 entity-based sanctions were enacted during the same period, including sanctions on vessels and vessel operators. However, despite these restrictions and widespread international condemnation, Russia’s economy is still projected to grow by approximately 1.5% in 2025.

A key factor in Russia’s economic resilience is its ability to continue selling oil above the $60 price cap set by many Western sanctions. Over the past two years, the volume of Russian oil transported by shadow tankers has steadily increased, reaching 4.1 million barrels per day in June 2024, equivalent to 70% of Russia’s total seaborne exports. Most of this oil is shipped to China and India. In doing this, the dark fleet plays a critical role in keeping Russia’s economic lifeline intact.

However, more recent 2025 figures show the potential impact of sanctions when properly enforced. As authorities have improved their ability to spot and stop dark fleet vessels, the revenues generated from this fleet have begun to decline. In the first seven months of 2025, total oil and gas revenues fell by 19% year on year.

What Incidents and Accidents Have Involved the Shadow Fleet?

The shadow fleet faces a high risk of accidents because many of its vessels are ageing and poorly maintained. This danger is compounded by the routine practice of switching off a ship’s AIS (Automatic Identification System), which renders it invisible to other vessels and greatly increases the likelihood of collisions. Such risks are already affecting the wider maritime industry.

For example, on 20 February 2023, two shadow fleet tankers encountered serious difficulties in the Bay of Gibraltar and required assistance from tugs and a salvage ship. Both displayed classic hallmarks of shadow fleet operations, including a lack of proper insurance and recent changes of name and flag – one had switched to a Gabonese flag and the other to a Palauan flag.

Other recent incidents involving dark fleet vessels include:

- Petion (Cuban-flagged): Collided with another vessel off Cuba while carrying sanctioned Venezuelan oil (March 2023).

- Arzoyi (Panama-flagged): Ran aground near Qingdao, China (March 2022).

- Pablo (Gabon-flagged): Caught fire off Malaysia (May 2023); the crew was rescued, though three remain missing.

- Turba (Cameroon-flagged): A 26-year-old vessel last inspected in 2017 lost engine power 300 km off Indonesia (October 2023).

- Unnamed vessel (Cameroon-flagged): A 23-year-old ship carrying Venezuelan oil required rescue by Indonesian salvage teams (December 2023).

What Impact Are Dark Fleet Sanctions Having on Russia?

Despite facing sanctions and widespread international condemnation, Russia’s economy is projected to grow by 1.5% in 2025, as previously mentioned.

Sanctions intended to block Western goods from entering Russia have proved porous. Products are being rerouted through countries such as Georgia, Kazakhstan and China, where they are resold to Russia at a premium. This has created lucrative opportunities for Russian small businesses to purchase sanctioned goods abroad, bring them back, and sell them domestically. Others have begun manufacturing previously sanctioned products themselves. As a result, the number of small and medium-sized enterprises in Russia has reached a record high. In 2025, growth in the number of small and medium-sized enterprises reached $6.7 million.

However, 2025 also showed clear signs that sanctions on the dark fleet are starting to impact Russia’s economy. In Q1 of 2025, Russia’s economy declined unexpectedly compared with Q3 of 2024. The sharpest falls were seen in excavator production, down 48.6%, and in titanium products, down 45%, reflecting a significant drop in investment “and evidence that Western sanctions are beginning to take hold.

Given the Complexity of Tracing Refined Russian Oil, What Strategies Can Authorities and Stakeholders Use to Effectively Enforce Sanctions on the Dark Fleet?

To understand this issue, it is useful to examine Russia’s oil flows. Most Russian oil shipped by sea goes to China and India. The value of India’s imports of Russian crude was $52.73 billion in 2024, representing a surge of 64,000% since 2013. Much of this crude arrives at the port of Sikka for refining into products such as petrol.

However, these refined products do not always remain in India. For instance, one tanker was tracked leaving Sikka, sailing around the tip of Africa, crossing the Atlantic, and arriving in New York. Shipments like this occur roughly twice a month, each carrying around half a million barrels of refined fuel. Once Russian crude has been refined, it becomes effectively untraceable, complicating enforcement efforts.

So, how can this trade be stopped? The first step is to identify the vessels involved. Operators must be made aware of which vessels are either subject to sanctions or considered high-risk. Next, those sanctions must be enforced, making it clear that any participant in Russia’s dark fleet network will be held accountable. For high-risk vessels not yet sanctioned, tools such as Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC can flag them, helping prevent any business engagement. Automated enforcement tools like this also help stakeholders avoid inadvertently supporting Russia’s shadow fleet.

How Do You Identify a Dark Fleet Vessel?

Identifying whether a vessel is part of the dark fleet is challenging. While certain “red flags” have been identified, emerging nuances make it difficult to categorise a ship definitively as “dark” or not.

Most identification methods rely on a sophisticated combination of satellite imagery, ship signals, and on-the-ground photographs. With this evidence, it is possible to expose the intricate network that allows Russia to continue exporting oil in defiance of Western restrictions.

OFAC Recommendations for Identifying Dark Fleet Vessels

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has outlined the following recommendations for industry stakeholders to identify high-risk vessels.

-

Proper Insurance

- Vessels must have continuous and adequate maritime insurance coverage.

- Ships should be insured by legitimate providers with coverage sufficient to meet Civil Liability Convention (CLC) and Oil Pollution Act (OPA) liabilities.

-

Classification Standards

- Ships should be classified by members of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS).

- Classification helps insurers, port states, and other stakeholders assess the seaworthiness of vessels.

-

Ship Tracking Systems

- Vessels must maintain continuous operation of Automatic Identification Systems (AIS).

- If AIS is disabled for safety reasons, the ship must document the reason for doing so.

-

Ship-to-Ship Transfers

- Transfers between ships may be legitimate but can conceal cargo origin or destination, potentially bypassing sanctions.

- Transfers outside safe waters increase environmental and safety risks.

- Maritime stakeholders should closely monitor and document all ship-to-ship transfers, ensure they occur in safe waters, and verify the origin and destination of cargo.

-

Cost Transparency

- Inflated or bundled shipping costs may be used to conceal purchases above price caps.

- All costs must be itemised at the start of the trade transaction.

-

Enhanced Due Diligence

- Increase scrutiny for ships with frequent administrative changes (re-flagging, name changes, ownership changes).

- Identify high-risk profiles based on age, incident history, deficiencies, or inspection history.

-

Reporting Requirements

- Anyone aware of potentially illicit or unsafe maritime oil trade, or breaches of the oil price cap, should report to authorities.

- International Safety Standards

-

Tanker Sales Monitoring

- Be alert for illicit purchases or evasive practices, particularly for ageing or recycled tankers.

- Conduct enhanced due diligence, including verifying ultimate beneficial ownership.

-

Sanctions Compliance

- Continuously monitor exposure to avoid dealing with sanctioned parties.

- Note that sanctioned vessels may attempt deception through renaming, reflagging, hiding IMO numbers, or falsifying documents.

-

Training and Transparency

- Develop targeted training programmes for employees and partners.

- Focus on the risks posed by shadow fleet activities and deceptive practices.

How Does the Dark Fleet Impact Shipping?

The rise of the dark and grey fleets is creating significant ripple effects across the global shipping industry. One immediate consequence is that tankers are tied up in the dark fleet, reducing the number of vessels available for legitimate trade, driving up shipping costs, and constraining suppliers.

Another challenge is the difficulty of verifying whether transactions involving a given vessel ultimately fund illicit activities. For example, a ship may not be directly owned by the Kremlin, but if it is controlled by Russian exporters with close political ties, the revenue it generates can still support the war of aggression in Ukraine.

A further concern is the prevalence of older vessels in the dark fleet. More than half of these ships are 15 years or older, meaning poorly maintained vessels are still operating at sea. These older ships often lack modern safety technology and may not meet minimum international safety standards, increasing the risk of accidents and spills.

A striking example is the explosion of the oil tanker Pablo off the coast of Malaysia on 1 May 2023. Built in 1997 and slated for scrap five years ago, the vessel had instead become part of Iran’s shadow fleet. The Pablo, nearly empty after unloading cargo in China, was navigating the South China Sea en route to Singapore when it caught fire 37.5 nautical miles northeast of Tanjung Sedili, Johor, Malaysia.

Investigations suggest the explosion was caused by a build-up of flammable gas in the empty hold, ignited by a fire on the upper deck. The ship’s age and its status as part of the shadow fleet raised serious concerns about its safety and maintenance standards. Tragically, three crew members lost their lives, and oil from the vessel washed up on Indonesian shores.

Tracking the Pablo via Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC software revealed the vessel remained offshore for months as authorities struggled to identify its owners and insurers. With no known insurer, Malaysian authorities had to manage the incident themselves. Had the tanker been carrying its full capacity of 700,000 barrels of oil, the environmental and economic damage to the Malacca Strait, a critical shipping route with rich fisheries and productive coastal ecosystems, could have been catastrophic, potentially amounting to billions of pounds.

This incident underscores the risks posed by a fleet of ageing, unregulated vessels transporting Russian, Iranian, and Venezuelan crude. It highlights the urgent need for stronger oversight, tracking, and enforcement. Compounding the problem, many of these shadow vessels lack proper insurance coverage, often relying on unknown, inadequate, or fraudulent policies. As a result, they are frequently unable to cover the costs of accidents when they occur.

What is the Grey Fleet?

Another term frequently used in the maritime industry is the “grey fleet,” a relatively recent phenomenon that emerged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Vessels are classified as part of the grey fleet when they appear legal on the surface, but their true ownership and origins are obscured, making it difficult to determine whether they are operating lawfully or in compliance with sanctions. These ships primarily transport Russian oil to countries that have not banned trade with Russia, such as China, Turkey, and India.

However, Pole Star Global does not draw a strict distinction between dark and grey fleets. The team takes a data-driven approach, identifying vessels as part of the dark fleet only when there is a heightened risk that they are circumventing the price cap. Rather than categorising every ship entering Russian waters, each vessel is analysed in detail to assess its risk profile.

In What Ways Could Sanctions on the Dark Fleet Evolve?

David Tannenbaum, Director at Blackstone Compliance Services, explains that sanctioning bodies, such as OFAC, continually assess the tactics employed by illicit dark fleet actors to stay one step ahead of illegal activity. Sanctions have evolved beyond targeting individual vessels to encompass the entire network of connected entities, including P&I clubs, classification societies, flag registries, corporate formation agents, and ship brokers. Recently, OFAC has also sanctioned digital entities in response to the growing threat of “zombie” vessels – ships that assume the identity of scrapped vessels by adopting their IMO or MMSI numbers.

“Other notable developments include the sanctioning of nuclear trade. The US continues to pay Russia approximately $1 billion annually for enriched uranium, which plays a critical role in powering 94 US nuclear reactors that generate about one-fifth of America’s electricity. Although Congress passed a ban on importing Russian enriched uranium in May, it will not take full effect for another four years. This leaves a challenging gap, as the US ceased domestic production of enriched uranium a decade ago and still relies on Russia for 25–30% of its supply. – David Tannenbaum, Director at Blackstone Compliance Services

Can Countries Block the Dark Fleet?

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS):

- Innocent Passage: Vessels may freely navigate through a country’s territorial waters (up to 12 nautical miles from shore) as long as their passage is not harmful. “Innocent” means the ship is merely passing through or travelling to or from a port.

- Obligations: Ships must comply with local laws, including requirements to be seaworthy and properly insured. In practice, however, most countries avoid blocking shadow vessels on these grounds, as there is no global registry of such ships and enforcement can be risky.

- Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs): EEZs extend up to 200 nautical miles beyond territorial waters. Coastal states have rights over natural resources and offshore installations within their EEZs, but cannot block vessels unless those ships pose a threat to these resources.

When States Can Intervene:

- If a vessel enters ports or inner territorial waters, it can be denied entry or blocked. However, this offers little recourse against ships merely passing through territorial waters.

- Under the International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC), countries may act if a vessel poses a serious risk of an oil spill.

- The Search and Rescue (SAR) Convention obliges coastal states to assist people in distress within their designated zones, regardless of the ship’s insurance status or operational legality.

How to Vessels that Belong to the Dark Fleet: Real-World Examples

Crystal Ice (IMO 9332638)

The product tanker Crystal Ice was purchased by an anonymous owner between November 2022 and February 2023 for immediate deployment in Russian trades. The tanker is registered to a single-ship company in the Marshall Islands.

Crystal Ice called at Russian Baltic ports before sailing to international waters near Kalamata, Greece, a well-known area for ship-to-ship (STS) transfers of Russian crude and petroleum products. While STS transfers can be conducted for legitimate purposes, transfers in high-risk zones – particularly at night – are frequently used to evade sanctions.

It is unclear whether these transfers were conducted above or below the oil price cap. However, the fact that they occurred in a high-risk region signals a need for further investigation.

Crystal Ice is registered under the Marshall Islands flag, which appears on the Paris Memorandum of Understanding’s “White List,” indicating a strong safety record with very few detentions or deficiencies during inspections.

The vessel is managed by Singapore-based Executive Ship Management, responsible for both commercial operations and compliance with the International Safety Management (ISM) Code. Executive Ship Management confirmed that all three ships in its portfolio are insured through Maritime Mutual Insurance Association (NZ) Limited, a New Zealand insurer managed by Maritime Management Establishment, a company registered in Liechtenstein. According to Maritime Mutual’s website, the insurer is backed by A+ rated Lloyd’s syndicates, reflecting strong financial stability.

Maritime Mutual requires proof that vessels comply with oil price cap regulations, and Executive Ship Management also obtains written confirmation from shipowners that their vessels meet these requirements. The manager further confirmed that all necessary paperwork for STS cargo transfers is in place, with Executive Ship Management acting on behalf of the owners.

The Marshall Islands registry emphasised its strict approach to sanctions compliance. After reviewing risk intelligence databases, satellite tracking (LRIT and AIS data since 2022), and consulting with US regulators, the registry reported no evidence linking these tankers to the so-called “dark fleet.”

Under these conditions, such a vessel would typically be classified as a “grey ship.” However, Pole Star Global does not formally distinguish between dark and grey ships. Each ship is investigated on a case-by-case basis to positively or negatively identify it as a dark fleet vessel. Through this comprehensive analysis, the Crystal Ice has been positively identified as a member of the dark fleet.

Pole Star Global, together with partner Blackstone Compliance Services, has flagged the P&I insurer as high-risk, noting that vessels in its portfolio are frequently involved in risky activity. While Maritime Mutual is not currently classified as a “P&I Club of Last Resort,” all its tankers are closely monitored in Pole Star Global’s analyses.

Regarding the vessel’s operational activity, after its acquisition in November 2022, Crystal Ice first visited the Russian port of Ust-Luga. From February 2023 onward, it has conducted STS transfers with other tankers in the Kalamata STS zone, a hotspot for Russian oil trading, continuing through 1 September 2023.

Chemul Ships Management Company

Chemul Ship Management Company is based in the Marshall Islands. Previous reports have flagged this management company as high-risk, with some of its vessels reportedly engaging in dark fleet activities, while others appeared to operate normally.

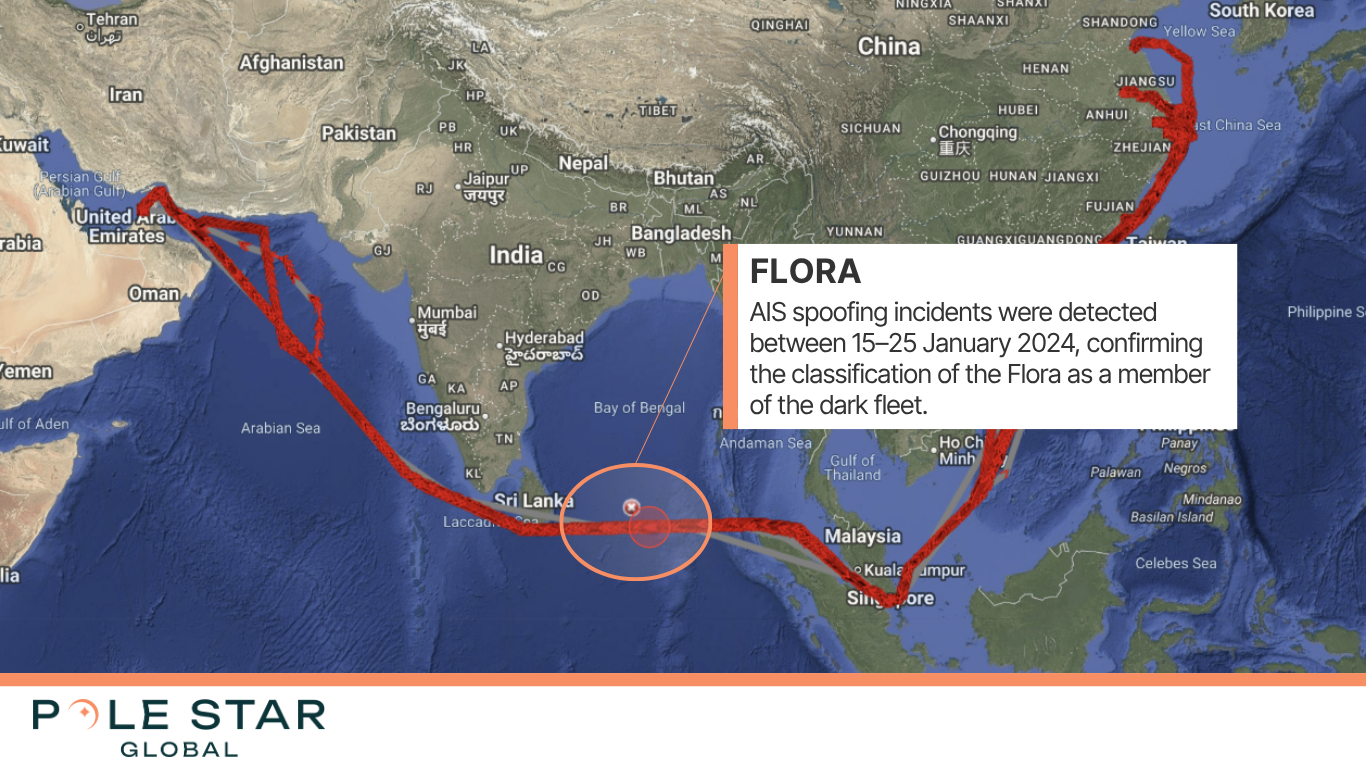

One vessel seemingly operating normally was the Flora. Its movements between Sharjah, Fujairah, and various locations in Asia did not initially raise any suspicions. However, Pole Star Global classified this vessel as part of the Dark Fleet due to its association with Chemul Ship Management.

The Flora was later reviewed again in June 2024, during which AIS spoofing incidents were detected between 15–25 January 2024, confirming this classification.

The complexity of these two examples showcases the challenges of identifying vessels as part of the dark fleet. To navigate this complexity, automated tools like Pole Star Global’s PurpleTRAC are essential. These tools combine satellite tracking, AIS data, risk intelligence, and historical patterns to assess each vessel comprehensively. By analysing movements, associations, and operational behaviour, these tools allow for the positive identification of dark fleet vessels, even when conventional indicators suggest they are operating normally.